Published online Jan 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.319

Revised: March 28, 2013

Accepted: April 9, 2013

Published online: January 7, 2014

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are an uncommon group of tumors of mesenchymal origin. GIST of the anal canal is extremely rare. At present, only 10 cases of c-kit positive anal GIST have been reported in the literature. There is no widely accepted treatment approach for this neoplasia. Literature is sparse on imaging evaluation of anal canal GIST, usually described as a lesion in the intersphincteric space. We describe the case of a 73-year-old man with a mass in the anal canal, and no other symptoms. Endoanal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging showed a well circumscribed solid nodule in the intersphincteric space. The patient was treated by local excision. Gross pathological examination showed a 7 cm × 3.5 cm × 3 cm mass, and histological examination showed a proliferation of spindle cells, with prominent nuclear palisading. The mitotic count was of 12 mitoses/50 HPF. The tumor was positive for KIT protein, CD34 and vimentin in the majority of cells, and negative for desmin and S100. A diagnosis of GIST, with high risk aggressive behavior was made. An abdomino-perineal resection was discussed, but refused. The follow-up included clinical evaluation and anal ultrasound. After 5 years the patient is well, with maintained continence and no evidence of local recurrence.

Core tip: Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are an uncommon group of tumors of mesenchymal origin. GIST of the anal canal is extremely rare. Here, the authors describe the case of a 73-year-old man with a mass in the anal canal, and no other symptoms. The patient was treated by local excision. An abdomino-perineal resection was discussed, but refused. After 5 years follow-up with clinical evaluation and anal ultrasound, the patient is well, with maintained continence and no evidence of local recurrence.

- Citation: Carvalho N, Albergaria D, Lebre R, Giria J, Fernandes V, Vidal H, Brito MJ. Anal canal gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(1): 319-322

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i1/319.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.319

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are specific KIT-positive mesenchymal tumors that are most commonly found in the stomach and small bowel. Anorectal GIST is rare and comprises approximately 5% of all GIST[1]. Although surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment, it is still uncertain whether local or radical excision should be appropriate for anorectal GIST[1].

A 73-year-old man was referred for evaluation of an anal mass. The patient did note an anal mass for the past 4 mo, without changes in size, pain or rectal discharge. Trauma to the area, rectal bleeding and fecal incontinence were denied. There was no weight loss or changes in appetite. There was no relevant past history.

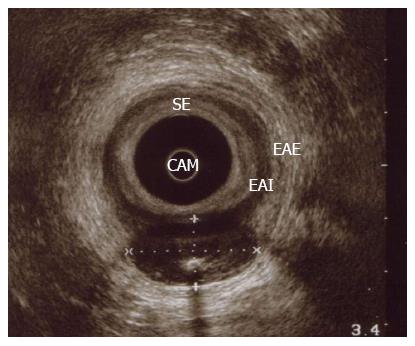

On examination there was a 4 cm × 2 cm left lateral anal mass, extending to the pubo-rectalis muscle, and firm and mobile over surrounding planes. No inguinal lymph nodes were found. Laboratory blood tests were normal. Endoanal ultrasound showed a left lateral isoechoic lump, with central calcification, extending from the inferior anal canal to the pubo-rectalis muscle. The lump was well circumscribed in the intersphincteric plane, pushing the external anal sphincter, with no evidence of invasion or infiltration of the surrounding tissues. There was no local lymphadenopathy (Figure 1).

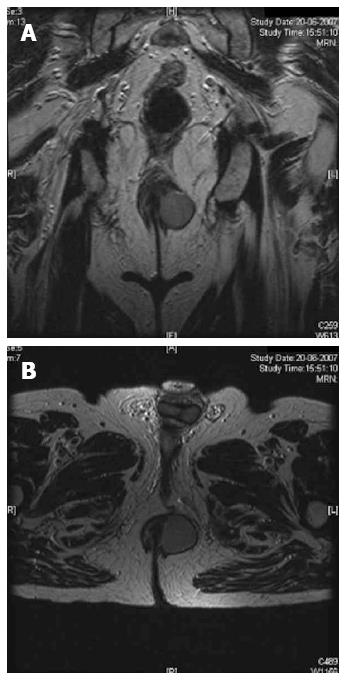

Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a well circumscribed, solid lump in the intersphincteric plane, without adenopathy (Figure 2). The patient was brought to the operating theatre and through a radial incision a local excision was performed. Only a small amount of fibers of the internal anal sphincter was also removed. The mass was capsulated and not adherent to the surrounding structures.

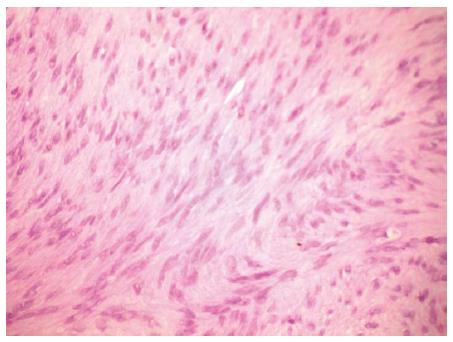

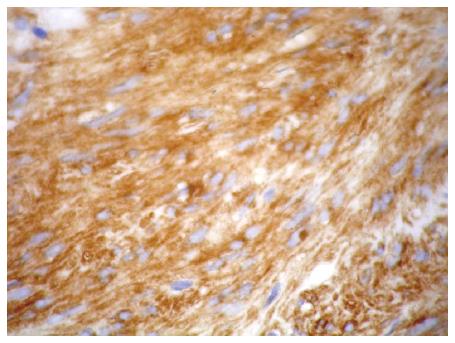

Gross pathological examination showed a 7 cm × 3.5 cm × 3 cm fibrous-elastic mass, and histological examination showed a proliferation of spindle cells, with prominent nuclear palisading (Figure 3). A complete margin-free (R0 resection) was confirmed; the mitotic count was 12 mitoses/50 HPF. The tumor was positive for KIT protein (CD 117), CD34 and vimentin in the majority of cells, and negative for desmin and S100 (Figure 4).

A diagnosis of GIST, with high-risk aggressive behavior was made. An abdomino-perineal resection was discussed, but refused. The follow-up included clinical examination and endo-anal ultrasound. After 5 years, the patient is well, and there is no clinical or imaging evidence of recurrence. The patient maintained fecal continence after surgery.

GIST is the most common nonepithelial tumor of the gastrointestinal tract[2]. The term was first used in 1983 to describe an unusual type of nonepithelial tumor of the gastrointestinal tract that lacked the traditional features of smooth muscle or Schwann cells[2]. These tumors have a histological and immunohistochemical structure similar to Cajal interstitial cells. In a very high percentage of cases (85%-100%), GIST and Cajal cells both express the c-kit receptor, which is the protein produced by the c-kit proto-oncogene.

DNA study of the tumor cells demonstrate a high frequency of mutation that leads to constitutive activation of the Kit-tyrosine-kinase in the absence of stimulation by its physiologic ligand. This causes an uncontrolled stimulation of downstream signaling cascades with aberrant cellular proliferation and resistance to apoptosis[3].

GIST cells are characterized by CD117 antibody, which identifies c-Kit, a membrane receptor protein with tyrosine-kinase activity. GIST express CD117 in up to 95% of cases, but also CD34 (70%), smooth muscle actin (40%), protein S100 and desmin (2%)[4]. Our patient had a c-kit positive anal GIST, and to our knowledge could be the twelfth case to be described in the literature[5]. Inhibitors of the tyrosine-kinase receptor, such as imatinib mesylate, represent the target therapy for local and distant recurrence after surgical resection[5]. GIST are found more often in the stomach (60%-70% of cases) and less frequently in the small intestine (30% of cases), while the rectum and anus are extremely rare locations with an incidence of 5% of all GIST. Anal GIST is even rarer representing only 3% of all anorectal mesenchymal tumors[5].

The vast majority of anorectal GIST afflicts males in the fifth to seventh decades of life. About half are incidental findings on colonoscopy or barium enema. The symptomatic group presents with either rectal bleeding, pain, change of bowel habit, signs of obstruction, or urinary symptoms akin to prostatitis[6]. Literature is sparse on imaging evaluation of anal canal GIST, usually described as a lesion in the intersphincteric space[2,5-7]. Calcification of a GIST has been reported in microscopic evaluation[8].

The best indicator of malignancy is the presence of invasion of adjacent organs or obvious metastatic disease seen on imaging or surgery[7]. The widely accepted criteria to predict malignancy of GIST are the mitotic activity (> 5 mitoses/50 HPF) and the tumor size (> 5 cm)[5]. No lesion can be definitely labelled as benign[5]. The treatment of choice for GIST is excision. High grade tumors are usually larger and need wider excision[5].

There are presently few published data on the outcomes of anorectal GIST treated by local excision vs radical clearance. Local recurrence frequently precedes late spread to the liver, lungs and bone, and has been attributed to inadequate surgical clearance[6].

Some authors recommend abdominoperineal resection for GIST larger than 2 cm[6]. Local excision can be an acceptable treatment option in selected patients, with tumors < 2 cm and < 5 mitoses/50 HPF (frozen section)[1]. Extensive lymph node dissection is unnecessary because GIST rarely metastasize to the regional lymph nodes[3].

In a series of 18 anorectal GIST, 6 out of 10 tumors treated by local excision recurred, whereas none of 8 tumors treated by abdominoperineal resection recurred. However, the method of resection did not significantly affect the development of metastasis or survival, as the number of metastases and deaths were similar with both surgical methods[9].

Local excision has the advantage of minimal morbidity and sphincter preservation, while radical excision may offer a better oncological cure[1]. The role of adjuvant therapy is still uncertain. Although inhibitors of tyrosine-kinase receptor need further study before their routine use as adjuvant therapy, their role in cases of distant or local recurrence has been accepted[5]. Neither radiotherapy nor conventional chemotherapy has any proven efficacy as adjuvant therapy[1,3].

Close patient follow-up is mandatory to disclose as soon as possible local recurrence or metastases[6]. A long latency period is common between the primary surgery and recurrences and metastases[8]. Recurrence 10 years after resection of the primary tumor is not rare. Therefore, all patients with anorectal GIST should be regularly followed up for an indefinite period. If recurrent disease is detected, further excision can be attempted, for cure or palliation. For unresectable primary or recurrent GIST, the use of imatinib has been shown to be effective in reducing tumor volume and controlling disease progression[1]. The natural history and prognostic features of GIST need further research[7].

P- Reviewers: El Nakeeb A, Regadas FSP S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Li JC, Ng SS, Lo AW, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Leung KL. Outcome of radical excision of anorectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors in Hong Kong Chinese patients. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26:33-35. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Hong X, Choi H, Loyer EM, Benjamin RS, Trent JC, Charnsangavej C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: role of CT in diagnosis and in response evaluation and surveillance after treatment with imatinib. Radiographics. 2006;26:481-495. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 132] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | De Marco G, Roviello F, Marrelli D, De Stefano A, Neri A, Rossi S, Corso G, Rampone B, Nastri G, Pinto E. A clinical case of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor with a peculiarity in the surgical approach. Tumori. 2005;91:261-263. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Lopes JM, Gouveia A, Pimenta A. O papel da anatomia patológica no diagnóstico e prognóstico dos GISTs. Revista Portuguesa de Cirurgia Junho. 2007;2ª Série, Nº 1:35-38. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Nigri GR, Dente M, Valabrega S, Aurello P, D’Angelo F, Montrone G, Ercolani G, Ramacciato G. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the anal canal: an unusual presentation. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5:20. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tan GY, Chong CK, Eu KW, Tan PH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the anus. Tech Coloproctol. 2003;7:169-172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Huilgol RL, Young CJ, Solomon MJ. The gist of it: Case reports of a gastrointestinal stromal tumour and a leiomyoma of the anorectum. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:167-169. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miettinen M, Furlong M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Burke A, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors, intramural leiomyomas, and leiomyosarcomas in the rectum and anus: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 144 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1121-1133. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 412] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tworek JA, Goldblum JR, Weiss SW, Greenson JK, Appelman HD. Stromal tumors of the anorectum: a clinicopathologic study of 22 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:946-954. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |